(Firstly, isn’t ‘lived experience’ a tautology? What does the ‘lived’ add?)

All through my career, and for longer than the above phrase has been in oh so common usage, I have told students to avoid using the first person when writing analytical essays. I circle every ‘I strongly believe’ and each ‘It seems to me’ and talk about why it’s a no-no when talking to the class next lesson. It’s not ‘wrong’ per se, as writing essays, whilst reliant on a web of principles and conventions, has very few actual rules. Whether you like the slightly stiff pragmatism of Orwell, the not so slightly smug but nevertheless illuminating waffle of Russell or the modern confections of Pinker, the essay is a glorious form and one whose decline in popularity pains me greatly – and I welcome the variety of voices that one finds when leafing suggestively through collections of essay writers at the height of their powers.

But for students, I say, avoid the first person. ‘But why, sir?!’ they naturally cry, their moist eyes turned toward me like so many shining fruit, and I tell them. No-one cares what you think, Jenkins. Or they ought not to. The fact that you believe something is by far the least persuasive, and the least important, of all the reasons you could argue a thing to be true. It’s almost the height of bad manners, to believe that your personal views, of all the methods you could choose to persuade your reader, should be so very impressive. If what you are saying is true, or at the very least, if your argument is sound, then it matters not a fig how strongly you believe it. Indeed, adding your own voice to what should be the inexorable flow of premises and evidence into conclusions could actually make it seem less credible.

If I, Jenkins, were to argue flawlessly that people not wishing to die young should not smoke tobacco, is my argument weakened if I am revealed to be a smoker? Not a jot! It makes me a hypocrite, certainly, and a fool, but the argument or statement or analysis is true within itself or faulty within itself. The identity of the author, utterer or arguer should make no difference in a world of reason and proper argument. At which point I would sit down, to their adoring indifference.

So, imagine my disquiet as the primacy of ‘lived experience’ over reason and logic has grown. Now, there are of course some debates where personal experience is of great import. If I am describing the effect that something has had on me, for example, a situation where I took offence but the offender claims none was meant, then that debate might reasonably involve explanations of why I reacted the way I did so they can be examined for reasonableness. But consider, dear reader, the debacle on Question Time just the other day, timestamp 39:00 https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b0blwgh7/question-time-2018-04102018.

Of course, one hesitates to wade into any debate that involves siding with a white man over two members of ethnic minority groups, but one must follow the train of reason wherever it chooses to go.

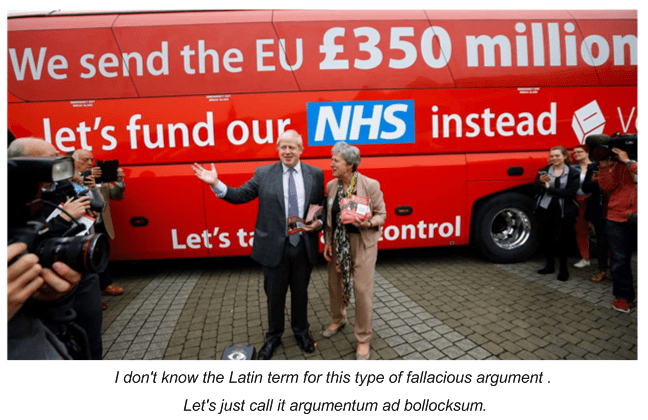

There is not, I hope, any need to explain why the gentleman on the panel and the woman wearing the hijab have made fools of themselves, and one would hope that, upon reflection and away from the emotive atmosphere of a live debate, they both feel more than a little silly. In their desire to emphasis the fact that they and those like them have been disadvantaged by something beyond their control – a fact with which I have no argument – they claim that said disadvantage allows, in the case of the gentleman on the panel, to declare as invalid the statement ‘Britain is the least racist of many European countries’ because it was made by a white speaker. Now, to evaluate that statement, what would we need? Data on millions of people over a period of, what, a year? Five years? Statistics from police on recorded instances of race-related crime, estimates of unrecorded levels of race-related crime, data on wealth distribution, access to education and services, broken down by race and, by all means, the reports of the experience of a big enough sample of people to allow us to make inferences about the countries in question. Then we can start evaluating the statement ‘Britain is the least racist of many European countries’. Being stopped and searched for nothing, prejudicial as that may have been, gives the gentleman on the panel none of those things. For the woman in the audience to imply that the original speaker’s whiteness, or the unlikelihood of him having experienced these things, invalidates his claim is similarly fallacious, a word my students always want to be rude, but, alas, isn’t. It is an argumentum ad hominem, one of the most misunderstood of the fallacious arguments. Ad hominem attacks are NOT just when someone insults you during an argument. It is when they claim the quality for which they insulted you, by its nature, invalidates your ability to argue what you are arguing. It is the first fallacious argument taught in any course on spotting fallacious arguments because it is the most common. And that was before the rise of identity politics.

Teaching students to argue is one of the hardest but most important parts of the job, and it would be pointless to comment in any depth about the disintegration of political and social discourse over the last several years; I’m sure you’ve noticed it yourself. But my great horror is not just that students and young people don’t know how to argue, but that correct argument is being replaced by this new cult of the lived experience.

As an English teacher, I’ve long had to defend my beloved subject (mainly from those blackguards in the Maths and Physics departments) from accusations that the study of literature lacks intellectual rigour, of the charge that ‘they can just write anything; no-one knows what the poet meant!’ And I say no. Good literary analysis can be as reasonable as a mathematical proof. Words have meanings. Yes, often more than one and, yes, they can change with context and, yes poetic or ‘literary’ language can be highly figured and dense… but the best literary criticism should be as well-structured as journalism or science. Read Frank Kermode for some good stuff. But, I am also well aware of the kernel of truth, that literature essays can be self-indulgent waffle if students do not learn to take themselves OUT of their analysis.

It’s up there with the most important things we can teach them. It’s not about you – start with what is known, which premises are agreed and which are disputed, what evidence is available to support your premises, are you ready to draw conclusions, if not, it’s off to the library with you. This cultish individualism offers, I believe, a greater threat to the intellectual life of this country than a potential Johnson premiership. I hope my strength of feeling is clear.