Define pathetic fallacy. Just a one sentence, working definition is fine.

Got one? Let’s do a check so you’re sure. One of these is an example of pathetic fallacy:

a) The sun shone brightly on the crisp autumn morning.

b) Jane stalked around the house, her emotions in turmoil, as outside the storm continued to flash and crash against her windows.

c) The benign sun and generally cheerful weather was at odds with Edward’s foul mood.

See one that matched up with your working definition? Excellent.

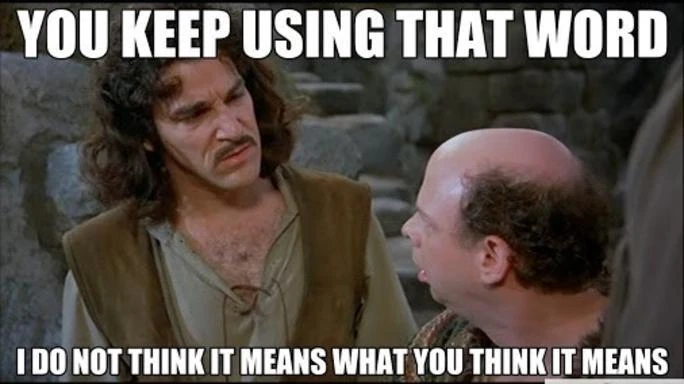

If you choose b), and/or if your working definition is something along the lines of ‘when the weather or setting in a story reflects the mood of the characters or plot’, then, alas, you are one of the vast majority who have a faulty definition of pathetic fallacy. Pathetic fallacy need have nothing to do with the characters’ mood, it’s simply a type of personification, when inanimate things, like weather, are described as having emotions. Therefore it is c) above, not b), because the sub cannot be benign nor the weather cheerful -it is a fallacy that they are capable of pathos. If you knew all that, well done. You, like me, are a massive, massive geek.

It’s one of those terms, so gaily slung around by students, that has wound up with a faulty definition in general usage – perhaps even in more general usage than the correct definition. You can see where it comes from – writers often use pathetic fallacy to say something about the feelings of a protagonist, and it’s often very powerful when they do, so these are over-represented in the examples English teachers use and there you are.

This happens with words and phrases all the time, of course, and is part of the rich mess of half understandings and workable misapprehensions that make up language. Sometimes these faulty definitions cause problems, though, especially when the faulty definition is arrived at disingenuously to further an ideological position. From Wittgenstein to Orwell, there was a powerful consensus in the 20th century that language in certain spheres was becoming unfit for use, such was its corruption and misuse, and it would be very sad if that happened in education.

So, off-rolling. Off-rolling at my school, and indeed any school, happens when someone with the appropriate authority – generally either myself or someone from the local authority, instructs the data-manager to remove a child from the school’s roll. That’s it. When you see statistics about ‘off-rolling’ that is literally all you know has happened. A child was on the school’s roll during last year’s census, and was removed from the school’s roll before finishing their programme of study.

But to see it used recently, one would think it were a sinister practice involving the abandonment of the most vulnerable by unethical headteachers to increase chances of looking good on results day. And the massive, massive problem is that sometimes that is what’s going on, and that’s a practice that may well be on the increase and against which the profession should be united in condemnation – but there is no way of knowing the extent to which it is happening based on DfE figures. Attempts to use these figures to draw conclusions about the practices of individual schools (and there’s been one in particular where elements of social media seem determined to use them to imply impropriety) tell you much more about the ideology of those slinging the mud than they do about the school.

Here, gentle-reader, are some scenarios. Every one of these is a form of ‘off-rolling’, and each of these students will show up as having been ‘off-rolled’ if the DfE ever chose to look into the statistics of this fictional school.

Scenario A

A headteacher sits at his desk. He is devastatingly good looking. He is in the middle of his weekly meeting with the deputy head, Mr Jeeves.

Headteacher: Right, so that’s the ‘jello incident’ dealt with. Now, you were going to update me on young Perkins, whom we haven’t seen so far this term?

Jeeves: Ah yes, sir. I received a letter from young Perkins’ parents yesterday. They are very sorry for the short notice, but Mrs Perkins has received an exciting promotion at work which takes the family overseas. They wish us all the best and thank you for what was a very happy two years for young Perkins.

Headteacher: Righto Jeeves. Drop a quick note to the data manager and have Perkins taken off-roll, would you?

Jeeves: Very good, sir.

Scenario B

The headteacher is in a reintegration meeting with the father of Watkins, who has not yet joined the meeting. Watkins is returning from a fixed period exclusion for letting off a stink-bomb during an exam.

Headteacher: The worry is, Mr Watkins, is that we’ve been here before. Your son has a great deal of potential, much of which he is on his way to realising, but he must show he is prepared to work on his behaviour. No-one expects him to be perfect from this point on – but I do expect an end to these premeditated acts of disruption. It’s not fair on the other students.

Mr Watkins: And if he does it again, headmaster, will he be shown the door?

Headteacher: I couldn’t possible prejudge a future event, not give an ultimatum. I owe it to your son to judge anything and everything he does on its own merits. Having said that, I cannot deny that permanent exclusion is now a real possibility if there were to be a repeat of this kind of deliberately disruptive behaviour.

Mr Watkins: I just don’t know what gets into him, he’s like it at home, he’s always sorry at the time then two days later he’s at it again. If he gets kicked out that’s it for him – I’ve seen those kids in the local PRU, he wouldn’t last five minutes in there.

Headteacher: Well, certainly that’s not what any of us wants to happen, and so when he joins us in here I want the message to be about how imperative it is that he…

Mr Watkins: What are my options?

Headteacher: I’m sorry?

Mr Watkins: If I don’t want to risk it? Can we move him to another school?

Headteacher: Hesitatingly Well…. it’s unlikely, I mean, we’re in January of Year 11, I can’t imagine many schools would take an admission at this late stage, nor, Mr Watkins, would I recommend it. Your son needs stability, he just needs to realise that…

Mr Watkins: What about if we keep him at home and just send him in for the exams?

Headteacher: No, no he needs to be in school, it’s the law, unless you elect to home-school, which I certainly wouldn’t…

Mr Watkins: How does that work?

Headteacher: Well, you apply to the local authority and the elective home education service visit you, and there’s an interview, but I cannot stress strongly enough that that is not in your son’s best interests. It sends the message that…

Mr Watkins: I’m sorry, headteacher. I can’t risk him going to the PRU. Thanks for all you’ve done.

Leaves.

A week later, a letter arrives from the local authority, confirming that Watkins is now being home-schooled. The letter is forwarded to the data manager, with instructions to take Watkins off roll.

Scenario C

A headteacher sits in his office. He has a thin, waxed moustache, the end of which he twirls in his caddish fingers. He is in a reintegration meeting with the parent of Jenkins, who has not yet joined.

Headteacher: So there you have it, Mrs Jenkins. He was caught in the act and admitted it as soon as questioned. It was only because I genuinely want what’s best for the boy that I didn’t permanently exclude then and there.

Mrs Jenkins: So you think he can turn it round, headmaster?

Headteacher: Alas, no. Your son is too far down this particular path to turn back now. If he comes back into this school I’m afraid it will be only a matter of time before I’m signing, with a heavy heart, the letter to permanently exclude.

The mother wells up.

And then it’s the pupil referral unit. Any vices your son hasn’t yet acquired, and I assume there must be some, I guarantee he will learn in there. Mixing with the worst possible sort, you know, real ‘wrong ‘uns’ as my mother would have called them, and from there it’s just a short step to the criminal justice system.

The mother sobs. The headteacher twirls his moustache.

There is…. another way, you know.

Mrs Jenkins: There…. there is?

Headteacher: Oh yeeees. I mean, between you and me, I like your son, I would spare him all of that….

Mrs Jenkins: Oh yes. Oh please!

Headteacher: I mean, I really shouldn’t really be telling you this, the government say we’re meant to let these things take their course, but….

Mrs Jenkins: Yes?

Headteacher: Turns away No, no I mustn’t, it isn’t… by the book.

Mrs Jenkins: Please! I won’t tell anyone! I promise!

Headteacher: Well, you know you have the right to simply remove your son? Just let the local authority know you want to home-school, fill in a couple of forms, and hey presto.

The meeting ends with Mrs Jenkins sobbing her thanks.

A week later, a letter arrives from the local authority, confirming that Perkins is now being home-schooled. The letter is forwarded to the data manager, with instructions to take Perkins off roll.

I could go on. And on. And this is before you get into schools whose rolls aren’t full, where students can come on and off roll with dizzying rapidity. Now, of my three silly scenarios, and I’ve been deliberately facetious because the real versions of these conversations are no laughing matter, one of them is evil. And I don’t doubt it’s on the rise. I know schools where I’m sure it’s happening.

Ofsted, (in this piece https://educationinspection.blog.gov.uk/2018/06/26/off-rolling-using-data-to-see-a-fuller-picture/) have got wind of higher than expected numbers of off rolling in some parts of the sector, both geographically and structurally, and are looking into it. Good for them – it’s exactly the sort of thing they should be looking into. Even they, however, admit that “Unfortunately, it’s not possible to know the full story of where pupils went to, and why, from the school census data alone” and “It’s not possible to know from the data available the reasons why so many pupils are leaving a school, and whether those moves are in the best interests of the pupils”.

So, yes, a school has a huge numbers of students leave roll, by all means hold the school to account and ask. (If, by the way, and to stick my head above the parapet, the answer is ‘a new head came in, said how it was going to be, a chunk of students decided it wasn’t for them and left’ then I’m not sure anyone’s done much wrong there.) But don’t sully the debate by claiming ‘off-rolling’ is always a variant of scenario C, or it will become another ‘pathetic fallacy’, a term where the inaccurate definition is in more common usage than the correct one, but this time to the great cost of an important debate.